in times of Covid-19 | June 4th, 2020 | by Lea

In the first few days of the pandemic I found it hard to concentrate on anything other than the number of cases and the various restrictions. Even the struggle for free seeds fell temporarily into the shadows of all the daily reports and general upheaval. Now I realise how wrong I was since many of the reports were simply pointing out the weaknesses in our society. The way in which we nourish ourselves is one of the hurdles we need to overcome. Here are five reasons why we need seeds to become common property now more than ever.

[The term commons is unfamiliar? Here is a video to fill you in.]

1. Seed commons put an emphasis on self-sufficiency rather than dependency.

The global food system is in many respects dangerously instable. When export is banned in one country, it can lead to food shortages in another. When schools shut, many children don’t get their lunch and those who aren’t allowed to go to work quickly end up knocking at hunger’s door. [1]

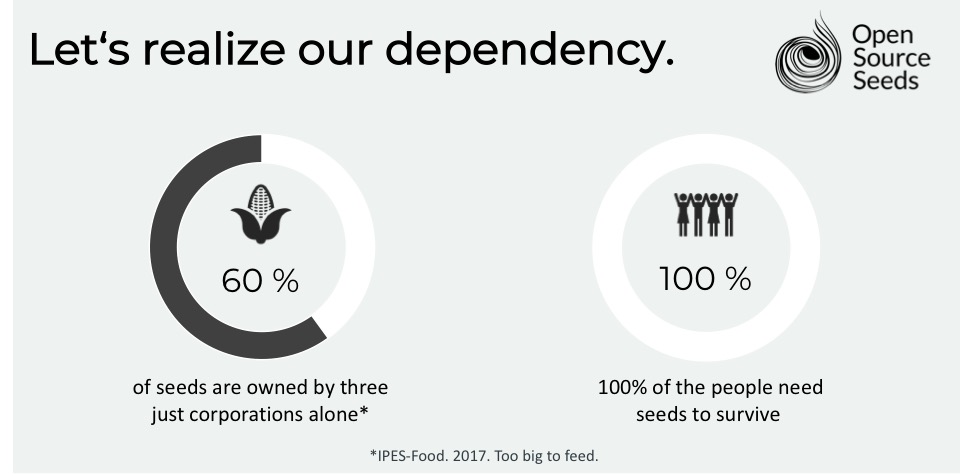

The food sector is predominantly made up of a few large businesses on which we are considerably dependant. [2] The market concentration of seeds is particularly high with more than 60% of commercial seeds being controlled by just three corporations. [3]

At the beginning of the pandemic some were given a fright by the almost empty supermarket shelves standing before us. For the first time many of us became aware that shelves don’t fill themselves. We suddenly realised the extent of our dependency and it makes us wonder about alternatives.

Open-source seed is one such alternative in that it is creating a seed commons, in which seeds are freely available for all. This allows for diverse and decentralised plant breeding on which a fair, ecological and regional nutritional system can be based.

2. Seed commons encourage regionalisation.

In the German media there have been many reports about the lack of seasonal workers who were not allowed to enter the country due to the travel ban. But even with the help of these workers Germany is far from being able to provide for itself . Whilst around 2/3 of Germany’s vegetables and 3/4 of its fruit are imported, the country has a surplus of animal products whose feed requires a great deal of land use. [4]

In Germany and in many other places as well, we could benefit from more regional produce in many ways. Of course, regional value chains are less vulnarable to a lockdown [1], but beyond that they are just as beneficial for the environment as they are for the regional economy.

However, the areas of breeding and seed production are still frequently excluded from supply chains. We therefore call for this to be changed and for the issue of seeds to be taken into account here. In order to facilitate biodiversity and regional adaptation, plants should be bred near to where they are cultivated, and their breeding shouldn’t be restricted. [5]

3. Seed commons strengthen communities.

Covid-19 has shone a light on the precarious situations of those working in agriculture and the food industry. These people have to continue their work to supply us with provisions despite the fact that hygiene measures, such as social distancing, are in many cases hard to provide. Not only are workers put at risk, but their crucial contribution to the food industry is poorly remunerated. [1]

This is where the social aspect behind the open-source concept comes into play. Open-source refers to the idea of common goods. Public property (“a commons”) is orientated around a society's demands and represents cooperation on an equal footing. Something, that has mostly been rationalized away in the essential professions revolving around health and nutrition.

4. Seed commons promote healthy agriculture.

Current research demonstrates that there is a close correlation between the emergence of new viruses and industrial agriculture. As well as amplifying the loss of natural habitats, industrial agriculture and the destruction of such habitats increase the frequency of interactions between humans and wild animals. This leads to infections becoming more likely to be contracted. Another area which poses a risk is intensive animal husbandry in which humans and animals come into frequent contact with one another. In healthy systems, however, natural regulatory mechanisms exist. They keep pathogens at bay and reduce the chances of contracting and transmitting viruses. [6]

This means that by making our agriculture more ecological and by using our land as sustainable as possible, we will be able to prevent viruses spreading. This requires diverse plant breeding that can offer suitable varieties in various locations.

5. Seed commons are part of the change we need right now.

A crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic can indeed knock the wind out of us and our industries. However, in most cases, we actually underestimate our own resilience. After we get over the initial shock and gravity of the situation, unprecedented waves of energy can be released.

Some may still ask for industrial approaches to solve the problem, despite them being responsible for poverty, food insecurity, climate change and massive disruptions in our ecosystems. But we’re also witnessing increasing demonstrations of public solidarity and activism towards those who are affected the most.

A number of governments acted quickly to protect workers and to ensure food provisions. A whole range of measures were put into place which had, at the very least, the inkling of what a new and resistant nutritional system could look like. For example, the Canadian province of British Columbia classified the work in communal gardens and at farmers’ markets as being system relevant. [1]

The knowledge we’ve gained from this crisis will continue to give momentum to the concept of seeds as a common good. This is particularly important because, even when Corona is finally over: climate change is not.

#FightEveryCrisis

References

[2] AGRIFOOD ATLAS - Facts and figures about the corporations that control what we eat, Heinrich-Böll-Foundation u.a., 2017

[4] (in German) Wie sinnvoll sind globale Lebensmittelimporte?, BR Fernsehen, 23.04.2020

[5] (in German) Vielfalt ermöglichen - Wege zur Finanzierung der ökologischen Pflanzenzüchtung, AGRECOL e.V., 2020